Naming the reality, protecting the name

A recent court decision states that for US consumers, Gruyère is a type of cheese, not a geographical origin. Some people are unhappy.

A cheese producer in Wisconsin is welcome to make a nutty hard cow’s milk cheese in the Swiss style and label it Gruyère, just as he might make an aged hard cheese and call it Cheddar (a name which, although representing the place the cheese style originated, has never enjoyed regional protection).

The French were the first with their regional naming control, their Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC). This means that wine, and cheeses, and some other products, that have a regional name (like Champagne) have to come from that region.

Initially, this was to deal with shadiness in the domestic market, to make sure that a buyer was actually getting Burgundy if that’s what it said on the label. The producers also wanted protection from low-quality competitors on the market. Later the AOCs were put into international agreements, too.

The EU brought lots of hitches when it came to harmonising these rules. In one case from 1994 (yes I learned about this at law school), a Spanish winery had to take the European Council to court over it. French and Luxembougish producers had claimed that the term “Crémant” could only apply to their sparkling wines.

Wait up, said Codorníu: the oldest winery in Spain. They’ve been making wine since 1551, and had trademarked their Crémant product in 1924. The court decided in Codorníu’s favor, that they could continue using the term they had been using for decades. There have been other cases, hinging on a producer using a name long before someone else tried to limit its application.

If you look at wine producers in Canada and Australia in the 1970s, they were labeling their products “Champagne”, “White Burgundy”, “Chablis”, etc. But this changed in the 1980s: they shifted to defining their wine by grape varietals, and calling their Champagne “Sparkling Wine”.

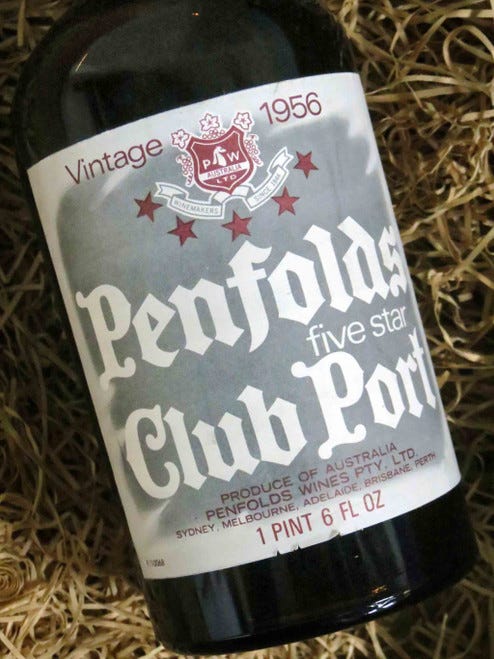

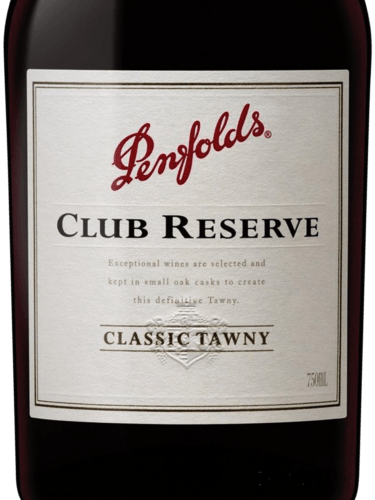

Penfolds, for example - a storied winemaker in Australia - is a producer of high quality fortified wine. The bottles from decades back call this product “Port”. Today’s bottlings however, say “Ruby” or “Tawny” - but never actually use the word Port. Because it’s a controlled term. Port has to come from Portugal. So they just use the adjectives, tawny, ruby, and leave the noun absent: because everyone knows what it is. They just can’t say it.

However, I’ve noticed in the last few years some of the old names creeping back. Wineries using regional terms again, for regions they are not in. Once again, “Burgundy” is being bottled in California.

And Gruyere can apparently be made anywhere.