Thanksgivings old and new

Today I'm going to talk about Thanksgiving foods and their history. The University of Illinois extension has some fun turkey facts, including that the average Thanksgiving turkey weighs 15lbs. I don’t think I’ve ever roasted anything larger than about 12lbs, but some of you are cooking birds weighing 30. Which means you need to have started defrosting it well before now! (A helpful twitter user has been counting down the days with thawing times).

But roasting a large bird for a winter feast was something that seventeenth century settlers (Thanksgiving’s creators) already knew. What makes Thanksgiving different are the side dishes that have emerged in the years since.

Ina Garten did a feature this year for the New York Times on how to do a store-bought Thanksgiving. But the whole point with Thanksgiving is that it has had these elements for a long time. People buy a frozen pie crust, tip in a can of pumpkin filling and call it a day. It's this convenience element that makes it such a distinctly American holiday: and also such a distinct conjunction between the traditional and the modern.

Thanksgiving itself is a wonderfully hybrid holiday, one that was invented to some degree through the nineteenth century (and particularly after the Civil War). As a national holiday not tied to a particular faith, it’s one that immigrants could easily join in. Creating traditions was a way for national identity to be formed.

The first Thanksgiving, whoever celebrated it and precisely when (whether or not it featured aliens), got molded into a story of the Plymouth Rock settlers and a harmonious feast with friendly natives - the story being spun even at a time when Indians were still being subjected to ethnic cleansing and violence. Some old-timey men with buckles on their hats and shoes roast a turkey and eat corn and everyone lives happily ever after.

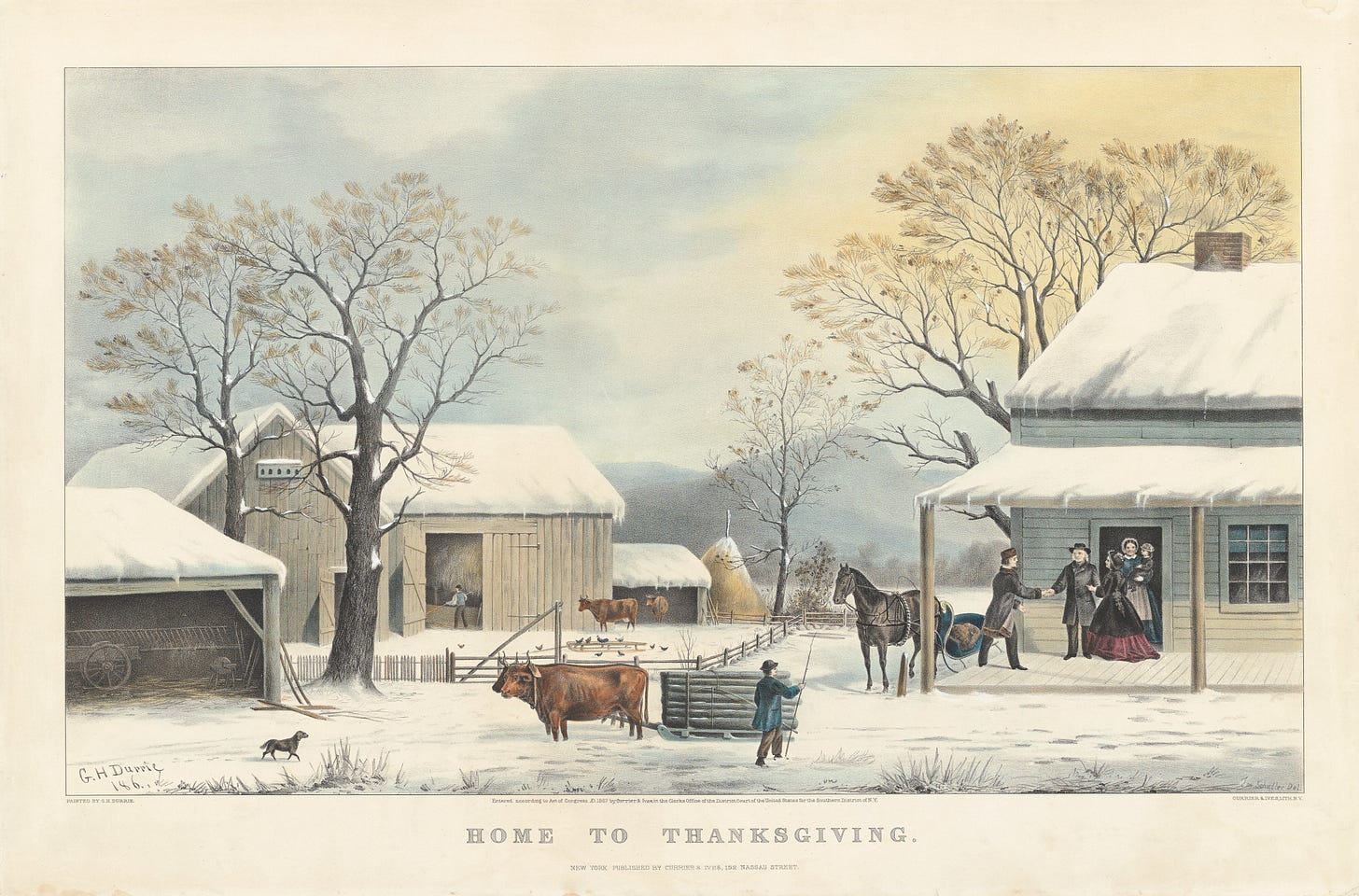

It was a way of creating a national narrative that lent itself to Currier & Ives prints and later Norman Rockwell images of wholesome Americanness.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Thanksgiving meal was taking on a standard form. Good Housekeeping in 1896 offered this Thanksgiving menu:

It seems pretty lavish (turkey and chicken pie?), not to mention a nightmarish number of side-dishes to have ready at the same time. Like cooking writers forever, the author suggests it won’t be such a big deal if “time is taken by the forelock” and you prepare half the dishes the day before. Sounds good, til you recall that most readers in 1896 didn’t even have electricity (and tutti frutti? That’s homemade ice cream. Which you can apparently just whip up, by hand, in between making pie crusts from scratch, ricing the potatoes and stuffing the turkey).

You’ll notice the presence of mince pie, which slowly dropped away from American holiday menus in the first third of the twentieth century. Thanksgiving menus of this time also often included English plum pudding, another Christmas adoption.

But Thanksgiving today features a couple of distinctive sides that don’t tend to appear at other meals. I’m talking about the green bean casserole and the candied sweet potatoes.

Dorcas Bates Reilly, who worked in Campbell’s test kitchen creating recipes, is credited with inventing the classic mushroom soup-bean casserole in 1955. The 1950s was a great era for “just open a can” recipes, led by the 1951 Can Opener Cookbook, by Poppy Cannon. A cookbook designed for busy women, it highlights the convenience of putting together several different ingredients all from cans. It saves the hassle of preparing fresh ingredients, you just tip canned ingredients straight into your casserole dish and into the oven. The recipes are easy, even if the result sound in some cases dubious.

Green bean casserole uses the notorious Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup, which features in a number of recipes Campbell’s have shared in their print ads, product labels, cookbooks and website (I say notorious because I hate mushrooms and yet the damn things pop up everywhere. When I have made the bean casserole I use cream of celery or cream of asparagus). But what makes it are the crunchy onion strips on top. These industrialized fried bits of tastiness are also a prepackaged ingredient, dating back nearly a century.

But even older than the bean casserole and the onion strips is the candied sweet potato with marshmallows. Sweet potatoes are native to the Americas, and were being cultivated in Central and South America before European arrival. The sweet potato turned out to be easy to grow in the US, particularly in the South, where it became a standard: sometimes replacing pumpkins and squashes in recipes.

For Thanksgiving, it also made the transition from savory to sweet - with a little boost from Campfire brand marshmallows. I don’t know when people started making sweet potato as a candied side - the Good Housekeeping menu above featured a savory sweet potato dish. The earliest version with marshmallows I could find was from 1916 (the stable manufactured marshmallow only hit the market in the early 1900s). But in 1920, Campfire brand brought out this cookbook which has at least FOUR sweet potato and marshmallow side dishes. Before people were opening mushroom soup for a casserole, they were opening a can of marshmallows and scattering them over sweet potatoes, and putting the dish in the oven.

(the recipe book has been fully digitized at Hathi Trust, if you want to get some recipe ideas!)

Finally, discussion of Thanksgiving can't go by without a discussion of cranberries. Cranberries - the variety cultivated for sauce and juice - are a species native to North America (although related species grow in Europe). They were adopted by settlers in New England in the 17th century for cooking and using their juice for dye.

For Puritans accustomed to English foods, cranberries would have seemed an analog to red currants: red currant jelly is traditionally served as a relish with game. If you’re keen, you can make cranberry sauce, though most of us encounter it in a jar or can. This has produced its own niche aesthetic, cranberry in its jelly cylinder fresh from being tipped into the bowl with a splunk - a celebration of industrialised food production. Something for which we should all be thankful.

Reading this celebration of blending industrial food with 'real' produce for special occasions is a reminder of how uptight us Europeans are. I could buy mint jelly online (a favourite with lamb) because no one seems to sell it in France. But I choose to make my own, from the kitchen garden. I fancy that this makes me somewhat classier.

Talk of Thanksgiving aliens brings to mind this Science Fiction flavored take on the encounter between the Native Americans and Europeans around Massachusetts Bay.

https://slatestarcodex.com/2013/11/28/the-story-of-thanksgiving-is-a-science-fiction-story/

But I really hope to try out a real mince pie at some point. I'm not much of a baker myself and I don't think I've ever seen one for sale.