Thrillseeking.....

Recently I was writing a piece on amusement parks, not the theme parks that are around today, but rather the historic kind that really flourished in the first quarter of the twentieth century, as an urban entertainment venue. (I hope that will be out sometime soon, and I can share a link).

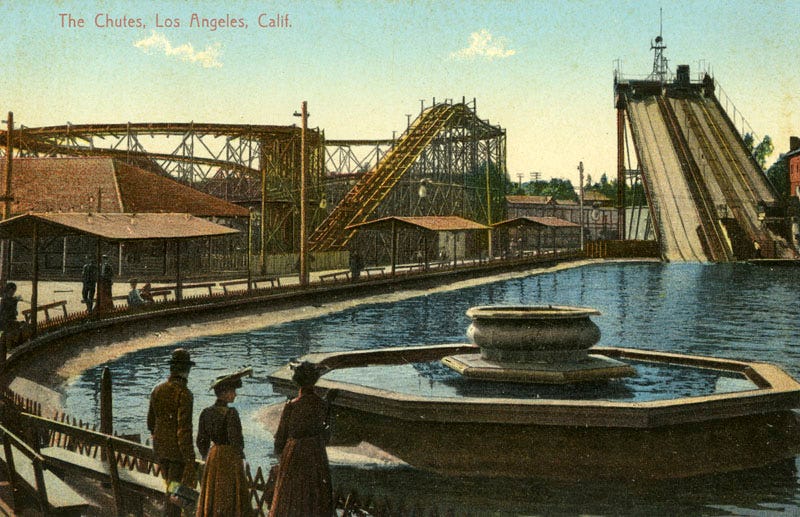

Since then I saw the news of a tragic accident involving a flume ride. There was a similar accident a few years ago to another park in Australia. Flume or log rides (“Shoot the chute”) were among the first attractions at modern amusement parks. Derived from logging chutes, they were the beginning of adventure rides. Chutes Park in Los Angeles was named for the ride, and there were similarly named parks elsewhere in California.

Of course, the rapids rides of today are much more sophisticated than those of 120 years ago. It seems with amusement parks that particular types of rides are replicated around the world, and the particular types of accidents that happen on them are replicated too. It's always been a challenge for amusement parks: ever since the race came for rides that were bigger, more dramatic, more scary. There are people who really enjoy the adrenaline response of fear, the kind of people who enjoy bungee jumping.

I can't say I'm among them, I've always been too scared to go on any roller coaster that takes you upside down. (Although statistically they're probably less risky than quite a few of the other rides: the speed and centrifugal force meaning you're going to be held into your seat). But it's a fine line when it comes to designing such thrill rides: that thrill is the operative word. People have to be plausibly scared. If something feels entirely safe, like riding on the teacups at Disneyland, you're not going to get the adrenaline rush.

Now obviously there are rides all around the world to capitalize on this kind of fear: like the Big Shot in Vegas. It apparently offers the experience of being shot 160 feet in the air at 45 miles per hour. You could not pay me enough to go anywhere near that thing.

But it's a challenge for designers to come up with something that is both scary, and safe at the same time. And it's a fine edge that parks have always had to deal with. (That's leaving aside the reckless and foolish designers who come up with something that is clearly dangerous for anyone involved).

They must play with our perception of risk, and as the pandemic has shown us, people’s understanding of danger is often out of touch with reality. The concern over blood clots from certain vaccines for instance, leading some people to avoid them: despite the fact that you’re more likely to get in a car accident driving to the vaccine clinic than suffer harm from the shot.

For most of us, our daily life is safer than that of our grandparents. Which leads many of us to crave danger, but also run screaming to a lawyer the moment anything untoward occurs. We want the thrill without the danger.

What else I’ve been up to: previewing the New Woman Behind the Camera show at the Met, and reviewing Carolyn Cox’s The Snatch Racket.