Why can't people do the right thing?

The covid pandemic has led to people being asked to do some things (wear masks, get vaccinated, socially distance, etc), which some people are less willing to do. I’m not here to get into the merits of vaccination or other measures, but to how we approach the idea of pulling together for the greater good.

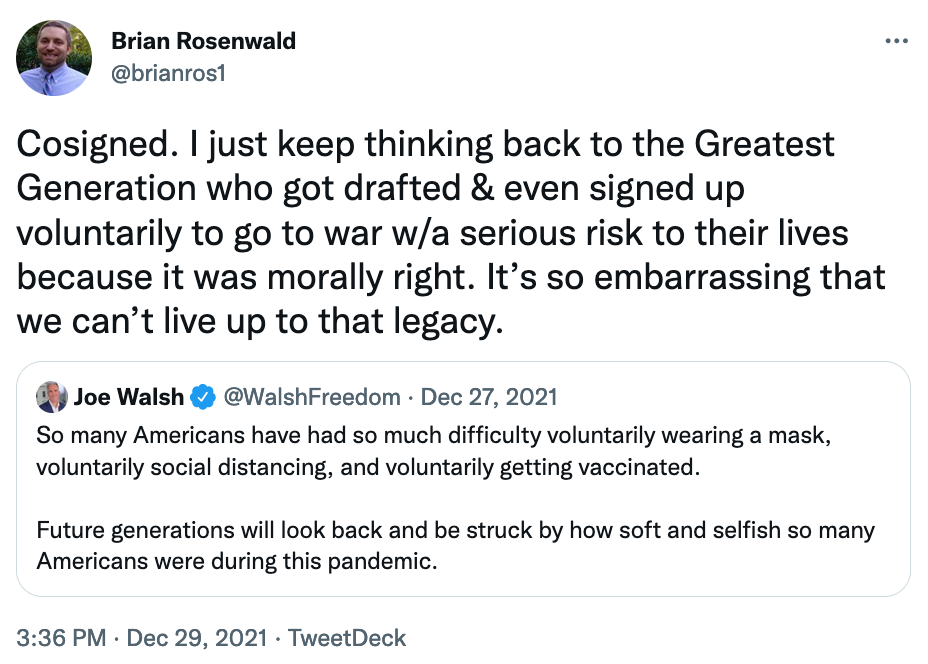

I’ve seen a few people making comments like this on social media:

And it’s an interesting question. Why are so many people digging in their heels on covid stuff. There are of course lots of reasons (people think coronavirus isn’t that serious; the rules keep changing; the rules seem not to apply to politicians).

But more broadly than that: you can't get people to “pull together” without people feeling like they're part of a society that they want to pull together for.

This is where I think governments have been going wrong. They jumped to “we’re all in this together” on covid (even as politicians’ public rule-evasion showed that no, they were not in it with us). But they needed a clearer definition of WE. When society - and its leaders - have been separating us and encouraging us to regard our neighbors as different to ourselves, it’s much harder to claim the WE when it’s needed. (An elite vibe that national identification, in the form of patriotism, is cringe at best and bigotry at worst is not helping either).

And this fraying of “us” has a longer history. Pulling together works well in communities of high social trust. Low-trust societies tend to be marked by tribalism, and doing what’s right for my group, where “my group” is not the national population, but my family/clan. In parts of the world where national leadership is unstable and capricious, this makes a lot of sense.

Indeed getting people to see themselves as part of a larger polity was one of the great social shifts after the enlightenment, which allowed the development of broader social programs (from the Bismarck era in Germany to the welfare state in Britain). It also required a lot of governmental stability (would you trust a government pension plan if you’d already seen two revolutions and a couple of coups d’état in your lifetime?). People had to trust that their systems were stable and non-corrupt.

People are also happy to contribute to things they see as helping people like them. That was the great sales pitch of the New Deal, and of Britain’s NHS (the National Health Service arrived at a time where people had just pulled together for the war effort, so the national mood was with it. I think if they hadn’t established it 70 years ago, it would be impossible to do so now). But that pull-together-to-help-the-group model has been harder since the 1960s, as levels of social trust, and trust in the government, have cratered, across the West.

(high social trust also tends to go hand in hand with other social factors, like ethnic homogeneity and Protestantism according to some scholars and these are key characteristics in the high-trust areas of Scandinavia).

Kai Erikson’s work on social deviance explaines a lot about the mechanics of social enforcement, and how it is about the group’s own identity:

the deviant is a person whose activities have moved outside the margins of the group, and when the community calls him to account for that vagrancy it is making a statement about the nature and placement of its boundaries. It is declaring how much variability and diversity can be tolerated within the group before it begins to lose its distinctive shape, its unique identity. - Kai T. Erikson, Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance, 1966.

Community trust comes with creating, and policing, boundaries.

That’s the flip side to the kind of enforced social conformity of the 1940s that got young men enlisting, and civilians joining scrap metal drives. There were some pretty strongly socially-enforced views on homosexuality, or interracial relationships - which most people don’t share today.

If you want social enforcement of norms, it means we need some “norms” to enforce, and it won’t just be masks.

I’m of the generation raised by boomer parents, who sent us all a message of “do what you want, be true to yourself, don’t worry about what other people think”. Which is great, liberating. But caring what other people think is the cornerstone of social enforcement. We can’t all “let our freak flag fly” and “ignore the haters” when the haters ARE the social enforcers. That’s how it works.

If I were zero in one of these many valid reasons, it would come down to WE. That definition has largely lost its meaning as large parts of society embrace a much more identitarian/tribal outlook. WE most often means US as opposed to THEM.

As a secondary reason, ubiquity of technology and our desire to play gotcha has made it all but impossible for prominent people to evade the rules they have decreed.

Interestingly, as I live in California and have watched Gavin Newsom do this repeatedly, it also seems that what was once known as the media is Gentleman's Agreement has also shifted purpose.

There was a tike when no one would have photographed FDR in a way that showed his disability, much less discussed it.

Now such gentlemen’s agreements are happily ignored if it makes “the other side“ look bad. And if one of US gets caught, well it’s fine if we give them a pass and except their condescending excuses without further scrutiny.

At this point, it is likely impossible that western society at least can abide by e pluribus unum.